Tabby Whitehouse-Banks explores how university living reflects a persistent gender gap in domestic labour, with women still taking on the bulk of household tasks.

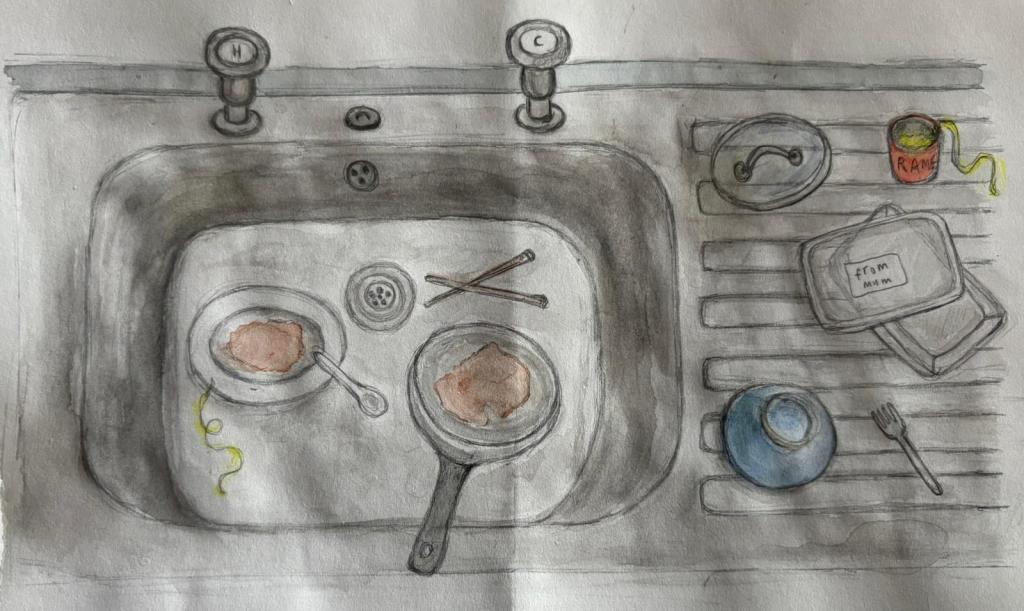

The transition to university denotes a pivotal initiation into adulthood, a domestic independence and an opportunity for self-responsibility. From the ever-overflowing bins to moulding dishes, a pattern emerges – and it is gendered. Yet many of our male counterparts arrive sorely unprepared for the domestic labour required in leaving home. Be it those raised with silver spoons, weaponised incompetence, societal expectations or learnt behaviour entwined with a seemingly invisible cognitive difference between individuals, the women of the flat become the bearers of domestic burdens.

It is a tale as old as time, so to speak, men falling short in domestic tasks like dishes, bins or general communal cleanliness, and their female counterparts absorbing the brunt of domestic labour, a shadow of archaic practices installed by the patriarchy. This perception or expectation that gender roles are a basic social exchange is driven by the currency of female labour. Think pre-1918 where women were desirable in their traditional form, a housewife, a mother, the ‘home front’, with the men of society being deemed as the ‘providers’. Women were deemed to have a natural affinity for domestic chores, not able to contribute to the workforce, politics or knowledge. Any woman who subverted such an expectation was perceived ‘unfashionable’ and undesirable, not a ‘proper’ woman.

An opinion that has resurfaced in the modern day through the TikTok glorification of ‘TradWives’. ‘TradWives’ represent the ideology and lifestyle centred around traditional gender roles, with the women embracing the domestic role of housework and child-bearing whilst being submissive to the man of the house.

Jumping into the 21st century: the modern woman and a progressive society … right? The burden remains a staple of society alongside the co-dependent husband. This is a by-product of boys often being praised for the bare minimum, whilst expectations for girls remain significantly higher, a consequence of weaponised incompetence being excused or normalised from an early age. So when boys posturing as grown men arrive at university assuming self-sufficiency, they expect their female flatmates to coddle them just the same.

University houses are simply a microcosm of broader societal norms, one that perpetuates these archaic gender roles. The danger of this dynamic is not just one of discomfort, it sets a precedent for the next generations, foreshadowing how young adults will shape their future domestic relationships, workforces and family structures. This male inadequacy in household chores or their apparent willingness to let the burden be a solely female responsibility within university halls and houses creates an invisible threat to a woman’s future. This is a threat not founded upon biological explanation but societal creation built upon existing behaviours.

A Cambridge study proposed the idea that the male and female perception of domestic action is one of these behaviours, a learnt behaviour. A suggestion that between individuals there is a gaping difference in ‘affordance perception’ with women’s subconscious urging them to ‘act’ when presented with a domestic task, like wiping the sides, and men’s subconscious seemingly absent of this urge.

These neurological differences in affordance perception mean that men often neglect domestic tasks when unprompted, with women again absorbing this burden. However, this study highlights that it is not rooted in a biological affinity for housework within women, but it is down to the nurturing of male privilege since youth. Then what transpires if a man is not raised in privilege? In my experience living with five boys as the only female in the household there is no black and white answer.

Private school or wealth does not necessarily signify domestic unreadiness; boarding schools often require a level of self-sufficiency. A parent’s decision to raise their children hands-on around the house instead of hiring a cleaner or maid instils a premise of self-sufficiency. The boys in my house exhibit behaviours ranging from inadequacy to indifference to complete self-sufficiency, although class and socio-economic background show no clear correlation. Yet before university, the boys at home were all catered for by their mothers to varying degrees, not from a lack of capability but because that is just how it was.

We need a cultural intervention, whereby parents stop allowing sons to opt out of domestic chores and where society must retire their exhausted excuse of male helplessness. It is not banal. It is not harmless. It is a quiet reinforcement of patriarchal power irrespective of cause, class, religion or race, and it starts with the primary socialisation from the ages of three to four, before children are even capable of completing chores.

So the next time your flatmate does not know how to do the laundry or the dishes, ask not why he cannot, but who never made him learn.