Annabelle Hart investigates the emergence of online feminist groups such as 4B and their efforts to reimagine a future for women that ‘decentres’ men.

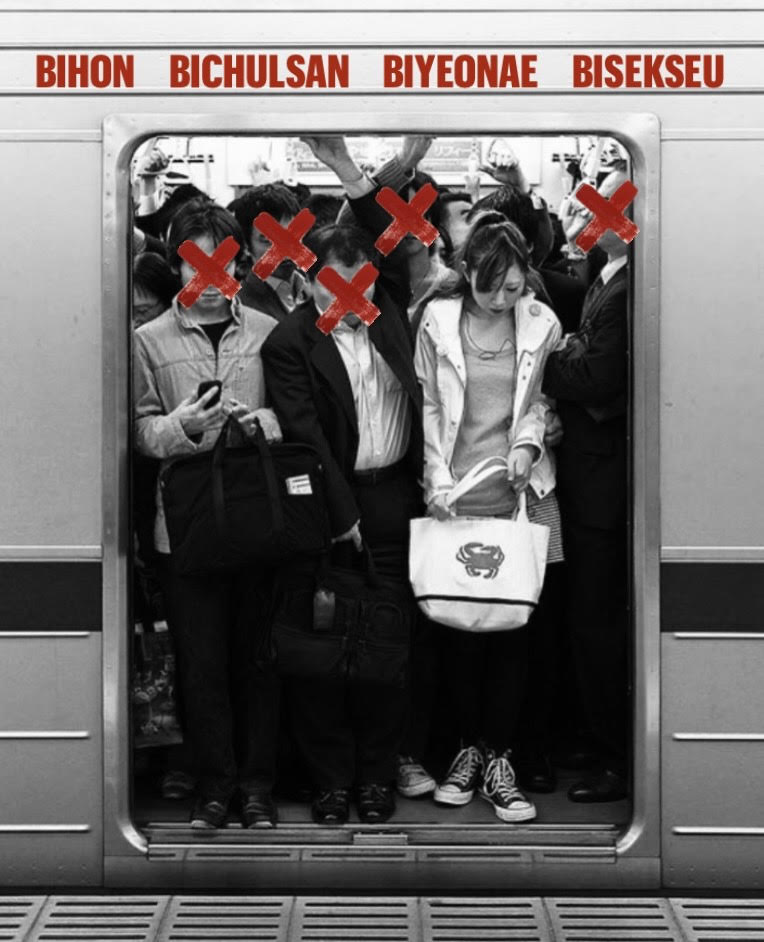

Radical online feminist groups evidence frustration amongst women towards institutional gender inequality, pervasive misogyny and male violence. Emerging in South Korea in 2010 and gaining wider popularity in 2019, the 4B movement saw women taking a pact to abstain from dating, marriage, sex and childbirth. Although the 4B movement is a small section of a wider tapestry of feminist action in South Korea, it garnered attention due to its radical nature.

Passive resistance mediated through online community groups marked women’s actions in response to the government’s inaction. The internet provided the space and tools for women to mobilise against misogyny, male violence and male ‘incompetence’. Break the Corset and Medalia are two other online feminist movements that aimed to subvert misogynist cultural norms. Medallia, or ‘mirroring’, trend saw women trolling men online, using mockery similar to that seen in #womeninmalefields on TikTok. Stereotypes used to harass women were reimagined to target men. Women bring perpetrators to justice in online spaces, whilst also allowing other women to express words of solidarity anonymously.

Yoon Suk Yeol, President of South Korea, galvanised support by expressing anti-feminist sentiment. He denied the existence of gender inequality whilst using online feminist groups as leverage to appeal to younger male supporters (1).

With South Korea having the second to lowest birth rates globally, the government has led a pro-natalist campaign encouraging women to have more children (2). The 4B movement has not caused the decline in birth rates. In reality, longer working hours, costs of high-quality education and a transition away from traditional family values are largely responsible (2). It is easier for politicians to attack marginalised groups advocating for change than to address the actual barriers to women having children. The supposedly idealistic nuclear family structure of past generations no longer translates into the present day for many women. Women are valued solely for their reproductive labour. Women’s bodily autonomy has been extracted and mapped (3). A womb symbolises a vessel bridging the gap between South Korea achieving a labour force for the future and escaping the potential strains of an ageing population. The government should urgently acknowledge women’s rights online and in everyday life.

Focusing on governmental control over women’s personal autonomy, Professor Jy Lee wrote ‘efforts to depolarise and de-stigmatise public dialogue around feminist issues could be a conciliatory step to ensure that women – as agents heavily implicated by state-level decision making about birth increase strategies – are being heard, represented and supported in the making of pronatalist designs, rather than being merely subjected to the latter’ (4).

The internet is a hostile place for women despite being a source of refuge. Digital sex crimes online group chats have been left unmonitored and deep fake pornography has been labelled a ‘national emergency’(5). This takes place in a misogynistic political landscape with the abolition of the Ministry for Gender Inequality, women comprising only 20 percent of South Korea’s parliament and little being done to address the gender pay gap.

The government continually attempts to nudge women to play as reproductive pawns whilst consistently undervaluing women’s rights as autonomous beings and refusing to take direct action to address threats to their safety (6).

The Wider Influence of the 4B Movement

Easily accessible feminist rhetoric means movements aren’t bound to their location of origin. Women in the US have adopted 4bs central principles to protest the fastening of governmental control over women’s bodily autonomy. With women’s reproductive rights being passed into the hands of men, the 4B’s allow for women to regain a sense of individual control over their bodily autonomy which the government seeks to regulate. Personal acts of political activism through abstinence signify a growing disdain towards misogynistic men in their lives and their refusal to cater to their desires.

Thumbs poised, I began some investigative scrolling through Tiktok. I found women advocating for the need to ‘decentre’ men from our lives. The extent to which one could commit to this idea differed greatly. Some women expressed no interest in engaging with men entirely. One woman spoke of not acknowledging or speaking to men in public settings, at work as well as cutting off friends. Others used the hashtag 4B more casually, threatening to leave their husbands to become “crazy cat ladies” due to men’s incompetence. Women who shaved their heads had to disable their comment section due to a flurry of negative backlash.

Abstinence from activities that supposedly bring enjoyment to women’s lives seems counter-intuitive. Surely women should not have to abstain from interacting with men to achieve political aims? Does severing ties with our male counterparts mean that we as women cannot experience womanhood in its entirety? The unravelling of the expectations for women’s futures exposes the long-held beliefs of what it means to grow old as a woman. Women should not be defined by their reproductive organs. It should not be assumed that women are responsible for unpaid labour in the form of caregiving in homes. Criticisms of the 4B movement expose the immutable value placed on women as birth givers and performers of reproductive rituals. Why should women have children if rights are only guaranteed to be given to the boys? Why have children when the institutional denial of gender inequality and gender-based violence has still been left unaddressed?

Jieun Lee and Euisol Jeong (2021) express how growing economic independence amongst women has allowed women to reimagine a future beyond domestic space and subservience to men (7). Although only a small portion of women partook in the online movement, nationally many women are reimagining a future defined by individuality and personal growth without leaning on a male counterpart (7). Women can find purpose without realising a traditional family which governments seek to enforce and incentivise. Women can dream and construct a future imaginary world which diverges from the traditional path (7).

The movement is not entirely inclusive. It has been critiqued for being exclusionary towards the trans community (8). The movement’s rejection of men fails to recognise how those who do not conform to the binary definitions of male and female are affected by societal misogyny.

On the surface, the 4B movement could seem trivial to some. No woman would actually abscond from men entirely. However, the movement is representative of a severance between men and women that is widely taking place. A dissonance exists between the aims of governmental policies towards women and the lived realities of many women. Childbirth and caregiving are promoted as patriotic whilst the personal needs of women themselves are systematically ignored. Online feminist groups with radical aims resonate with women when governments pose a threat to personal agency and bodily autonomy. Radical pacts and ideas are needed in the face of ludicrousness.

Reference List

[1] Gunia, Amy. “How South Korea’s Next President Capitalized on Anti-Feminist Backlash.” TIME, TIME, 10 Mar. 2022,time.com/6156537/south-korea-president-yoon-suk-yeol-sexism/.OECD (2019),

[2] Rejuvenating Korea: Policies for a Changing Society, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c5eed747-en.Lee, Jieun, and Euisol Jeong (2021) “The 4B Movement: Envisioning a Feminist Future With/in a Non-Reproductive Future in Korea.”Journal of Gender Studies, pp. 633–644, www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09589236.2021.1929097,https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2021.1929097.

[3] Lee, J. (2024) Towards an ethics of pronatalism in South Korea (and beyond). J Med Ethics.https://jme.bmj.com/content/medethics/early/2024/11/27/jme-2024-110001.full.pdfJang, B. (2022). Yoon Suk-yeol needs to change the way South Korea treats women. [online] Amnesty International. Available at:https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/05/yoon-suk-yeol-needs-to-change-the-way-south-korea-treats-women/.

[4] Press, Associated. “South Korea Pulls Website Mapping Women of Prime Age to Have Children.” The Guardian, 31 Dec. 2016,www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/31/south-korea-pulls-website-mapping-women-of-prime-age-to-have-children.

[5] Mackenzie, Jean, and Nick Marsh. “South Korea Faces Deepfake Porn “Emergency.”” BBC News, 28 Aug. 2024,www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cg4yerrg451o .

[6] “South Korea: Gender Distribution of Seats in Parliament 2024.” Statista, www.statista.com/statistics/1455106/south-korea-gender-distribution-of-seats-in-parliament /. Accessed 29 Apr. 2024.

[7] Quispe López. “Is the 4B Movement Trans Exclusionary? We Asked an Expert.” Them, Them., 19 Nov. 2024, www.them.us/story/how-4b-actually-leaves-trans-people-behind. Accessed 8 Dec. 2024.

[8] Elliot Sang. “Life without Men: The 4B Movement.” YouTube, 29 June 2024, www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkpmVPZVgV8