Abbie Holmes mediates on the content created for girls and the messages they express, exploring female made media and its positive influences.

As Christmas fast approaches, I find myself thinking back to my childhood. My personal Christmas classics were rather specific to me. As my mum would suggest ‘Elf’, I would cross my arms and insist on shoving 2008’s Barbie in A Christmas Carol back into the DVD player. Again. I sometimes begin to feel slightly bad for my mum, because this was not an event enclosed to December, this was year-round. To this day, I can proudly say I’ve watched all of Mattel’s forty-three straight-to-DVD (now streaming) Barbie movies and can recite the plot of most with extreme accuracy. I’ll admit that the intensity of my interest in Barbie was slightly fuelled by hyper-fixation. But through the haze of nostalgia and questionable animation, I stand by the fact that a lot of these films hold up, even with a more developed frontal lobe.

Now an adult, I’ve begun to look back on why I was drawn to low-budget media as a child. I watched Disney but was never that engrossed in it. My most watched Disney film was an old VHS tape of The Little Mermaid II: Return to the Sea (2000) which I greatly preferred to the original despite what I now recognise as an extreme decline in quality. The Little Mermaid II follows Ariel’s daughter Melody, as she rebels against her parents to follow her pull to the ocean. Compared to its 1989 original, there is not much of a romantic focus. Besides a brief dance with an unnamed suitor (which goes horribly wrong), the plot is entirely focused on Melody’s relationship with her heritage and family.

This is a trend that most Barbie movies follow, in fact, it’s a trend that most low-budget media for young girls follow. Even the Bratz movies, which are no stranger to a romantic subplot (lest not forget the iconic “who is that fine babe?”) their plots were still generally focussed on friendship and ambition. These pieces of media are central to a lot of our childhoods, so why is it that when the budget increases with the likes of Disney, the plots become so male-centric?

Much of the answer lies in how women and girls are considered as an audience, or rather how they’re not. The core of it is systemic: with men making up 76% of successful directors, writers, editors, and cinematographers, it’s less that women are maliciously ignored as an audience, but rather simply forgotten. Most successful (read: funded) films are aimed at a male audience. Unfortunately, it seems when men are making films directed towards girls, no matter what age, they cannot help but centre themselves. Much of this comes down to the fact that cinema as a whole is seen as a pastime exclusively for men, the 50% of women movie-goers seen as only tagging along with their male counterparts.

This is why, in a full-circle moment, Greta Gerwig’s Barbie (2022) was so important. In a world where only 30 of the top 100 films are led or co-led by women, Barbie proved to the film industry what they should have already known: that media for girls, by girls, is not just important, but vastly profitable. Though Barbie undeniably has its issues, that many women, on that successful a project, is almost unheard of.

This is even more vital to acknowledge when looking at the data in the years after Barbie’s release. 2023 saw a 10-year low in the number of female leads in successful projects, and only 11% were gender equal in speaking roles. It doesn’t take an overwhelming amount of critical thinking to uncover why our childhood selves were drawn to the low-budget media that undeniably centred us. It’s become an inside joke that not a single Barbie movie passes the reverse-Bechdel test, a statistic you’d struggle to find in any blockbuster series.

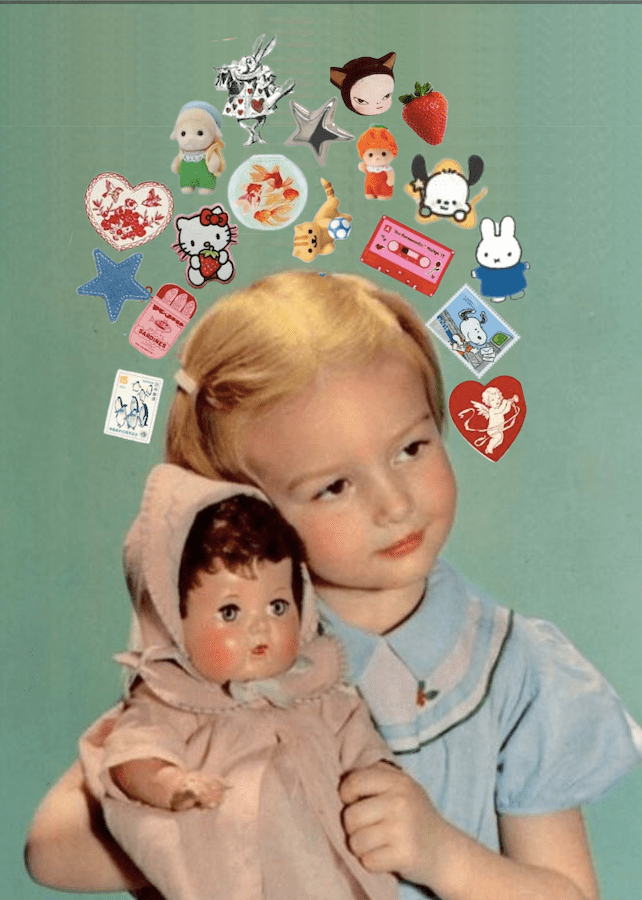

This ultimately leads back to a tried and true argument, the importance of representation. Though on-screen Barbie might be overly thin and overly blonde, it was nice to see her float away from annoying men with her best mate on a rainbow. Which, come to think of it, was probably seven-year-old-me’s dream afternoon. As young girls, we’re not particularly concerned with consulting men for answers. Our idols are our mothers, our friends, our teachers.

The question of representation, however, brings us to another undeniable issue. Early 2000s media for adolescent girls was not exactly the pinnacle for diversity outside of gender. Though Bratz was a step forward in regards to portraying ethnically diverse characters, most animated leading ladies in our favourite budget flicks were very white, very blonde, very thin, and very white.

This is particularly alarming because this media is catered towards children in their key developmental years. Media shapes how children build their perceptions about their own racial-ethic group, alongside others. When there isn’t any representation to form perceptions on, there’s shown to be a negative psychological impact towards children’s sense of self. Studies have shown a negative correlation between TV exposure and negative self-esteem in Black children and White girls – while emphasising a positive correlation for White boys.Hopefully, this is a problem we are slowly starting to see be fixed. The Barbie movies of the last decade have included a range of ethnicities and body types, the latest Netflix editions introducing a second ‘Barbie Roberts’, a Black character hailing from Brooklyn, as a foil to White Barbie from Malibu. Furthermore, there seems to have been a hopeful shift concerning high-budget children’s media. 2021’s Encanto told the story of a young Colombian Mirabel without being male-centric. Looking back at my childhood, I’m glad I had the media I did, but have come to realise many others do not possess that privilege. Going forward, I can only hope the next generation of girls can experience the joy I feel towards my childhood classics, without their pitfalls.