Lindsay Shimizu discusses the capitalistic commodification of hobbies and the societal distaste for ‘feminine’ downtime.

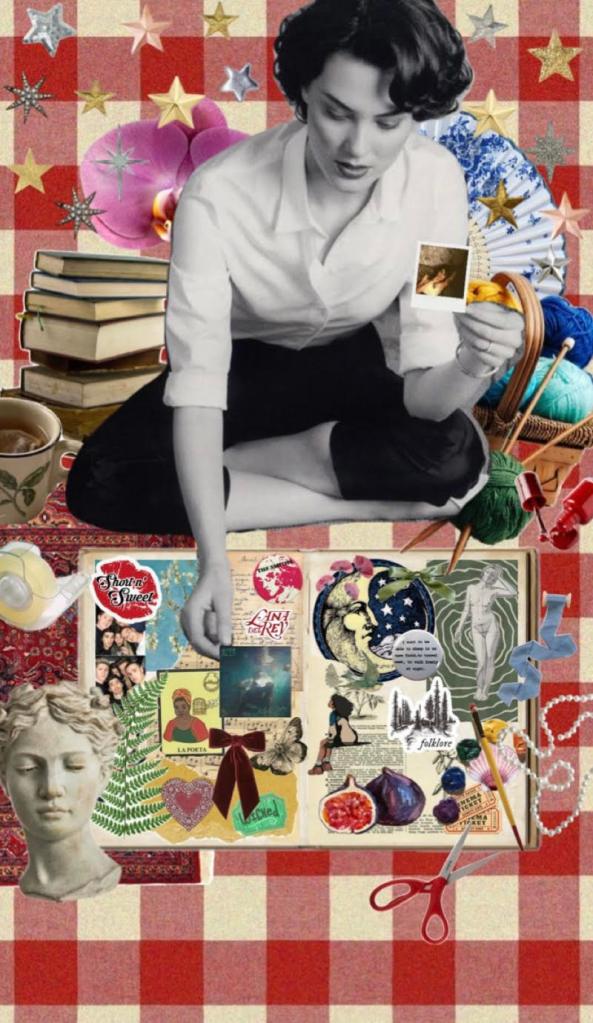

I am a girl proud of her many hobbies. Some obvious ones are reading, writing, baking, and crocheting, but I will also include watching TV and listening among the others. I am sure you would agree that it feels wrong to accept that all of these activities are indeed hobbies, but why?

It’s crucial to preface a conversation on hobbies by reminding ourselves that, as a society, we tend to condemn free time for being wasteful.

This is where the trouble begins – because of ‘internalised capitalism’, we equate self-worth with productivity. We celebrate crossing items off to-do lists, but when it comes time for a break, we feel guilty. Productivity is king and idleness is the enemy. To alleviate this ‘productivity guilt’, breaks have to be productive too, different from traditional 9-5’s, but a type of work in their own right. Hobbies, then, have pivoted from simply being recreational to being vehicles for self-betterment, or are even commodified into side hustles.

When deciding how to fill our free time, we teeter between choosing obvious, so-called productive hobbies like reading, learning new skills, or exercising and choosing the time-wasters. Because of the ‘I-should-be-doing-more’ mindset, breaks are only taken when ‘deserved’. By the time we’ve allowed ourselves to pause, it’s usually too late, energy is depleted, and relaxation itself is yet another ‘to-do.’

This ‘productivity guilt’ especially affects women. Like so many things, activities are needlessly gendered, and seemingly feminine hobbies are the idle ones. We’re quick to point out why certain activities seem to be wastes of time and we are ready to shame women for using breaks inefficiently without considering what makes these non-hobbies so prevalent and appealing in the first place.

Alongside the internalized capitalism and productivity guilt that everyone holds, many women feel like they carry an invisible workload of extra labour that goes unnoticed. Whether it’s doing domestic chores on top of a full-time job or performing more emotional labour in their jobs or relationships, women expend more energy. The inequality is so normalized that the burdens of being a woman (like being more alert when being alone in public) seem cliched. Thus a woman’s load is equivalent to the work of her male counterparts and sometimes even less than. And of course, gender is not the only factor in these invisible loads; race and disability among others intersect as well. I do not speak about this extra load to portray women as perpetually suffering, miserable, and tired, but rather to contextualize. If you factor in invisible loads, it’s no wonder why women might favour what’s less strenuous. Unfortunately, this links female hobbies and femininity to laziness and idleness in a frustrating contradiction.

I want to look at a particularly interesting example of the idle, female hobby: fangirling. The so-called time wasters like watching TV or listening to music are decidedly not hobbies. Not only does fangirling indulge in these activities, but it also celebrates them. I have always played the role of superfan, be it for One Direction or musicals, but I never considered the time I spent listening to albums or rewatching episodes as hobbies. When girls make video edits or connect with other fans on stan Twitter or memorize quotes by heart, these seemingly passive activities are seen as merely obsessive and frivolous. Participating in fandoms or ‘fangirling’ avoids neat definitions. The only requirement to be a fan is to enjoy something and engage with the content in some way. Fangirling doesn’t take effort nor does it ask you to improve yourself. It is the epitome of passing time purely out of passion. And by the way, men can and do fangirl all the time. Men do their best to evade unproductivity, denying that they too need a break. But I’d argue male sports fans cheering on their teams from the comfort of the couch are as idle as Love Island watchers, and that’s okay!

Let’s not forget that the meaning of hobbies is subjective and that gendering activities is extremely unnecessary. In our debates on definitions, we’re demonizing hobbies, especially the ones seen as more feminine, but according to the OED, an activity need only be done out of ‘amusement or interest’. Defining what we do is pointless. If we get bogged down by trying to label everything we do by criteria of productivity or even amusement, we replace actually relaxing with worrying. By the time we’re done running in circles, there won’t be time for any hobby or break at all.

There’s so much to say, but before we unpack the devaluing of women’s hobbies, I just want to say we deserve rest. It’s such an obvious, but forgotten sentiment so this is where I have to begin to conclude. This isn’t a ‘let women like what they like’ argument. We haven’t gotten that far. This is a ‘let us rest’ plea. Rest does not mean rotting all of the time. It doesn’t exclude self-improvement and the hobbies that invite self-betterment. Rest is the balance between work and leisure. It’s resisting the internalized ideas that we are wasting time. It’s remembering that the commodification of time is epistemological. Rest isn’t about female hobbies or whether we should redefine the word. Like I said, the definitions don’t matter. We must instead spend our time genuinely finding the activities enjoyable no matter how idle, engaging with them and trying to move past the guilt. There is so much work to do but the first step in any of it is to take a breath. To take a break. To waste time.