Alice Graham warns us about the blurred line between the passive consumption of controversial online content and the proliferation of shockingly sexist lifestyles.

This Summer, TikTok was ruled by Charli XCX’s Brat girl persona, the empowering party-girl aesthetic that was popularised by Charli’s personal brand marketing as a hedonistic, unhinged and undeniably hot female figure for the release of her album Brat. But, before this unconventional feminine figure took over, the controversially traditional ‘tradwife’ was in the spotlight. While social media trends shift quickly, the gender-political controversy stirred by the tradwife still lingers.

The tradwife, as the name suggests, identifies the women who romanticise traditional gender roles and promote the superiority of the wife and mother on TikTok and across social media. She is most often found in the kitchen of her perfect house or farm, looking fashionable yet modest, and cooking meals from scratch for her rich husband or family. In short, she is the enemy of the Brat girl in terms of her character and her audience. Both Charli XCX’s Brat content and the tradwife aesthetic have been competing for the attention of young women on TikTok. While the Brat girl’s popularity among this audience is unrivalled, the tradwife’s controversial celebrity cannot be denied. It is the co-existence of these two female figures, aestheticized in such different ways, but on the same For You Page, which is shocking.

The prominence of the tradwife trend, championing passé and apparently unfashionable feminine ideals, may seem surprising in our modern liberal age, but the aestheticization of ‘pure’ or ‘natural’ femininity seen in tradwife content is not a new concept in mainstream social media. In fact, the courteous tradwife could be considered a sister to the well-renowned ‘clean girl’ that occupied our screens in 2022 – a trend which similarly promoted ‘natural’ beauty as well as an unattainably sophisticated, polished lifestyle. It is understandable that such aesthetic imagery continues to entertain us – not only does its idealism provide us with a comforting escape from our own lives, but it can also provide us with a more attractive lifestyle to aim for. Surprisingly, we continue to long for the aesthetics of both these lifestyles despite knowing their problematic realities. We are aware of the tradwife’s sexist truth and even the exclusionary vision of both figures as rich white women, but still impressed by the charm of their content. Rachael O’Dwyer voices our inner monologue as we battle this guilty pleasure: ‘I understand that I am being sold a lie but I don’t want to think. I want to vibe. I want a date night. I want to get ready with her. I want an expensive candle’. This is definitely true for the clean girl aesthetic, and, for some, it might be true for the tradwife aesthetic as well.

For others, the entertainment of the tradwife figure comes from its controversial ideals. When pro-feminist beliefs appear to be the norm among women, how can you not be interested in the possibility that some are still telling their daughters that ‘women were created to work 24/7 inside of the home’?

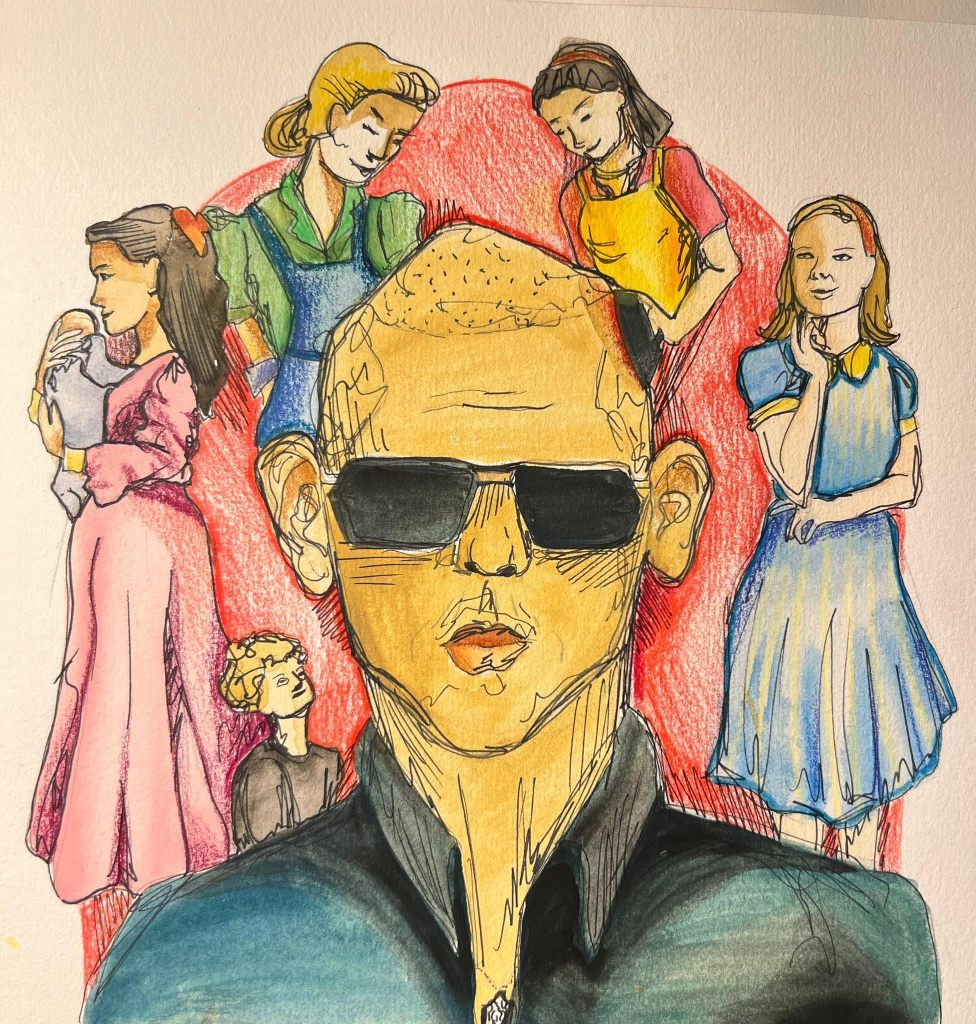

No matter what you think about the tradwife, good or bad, you are interested. With TikTok algorithms rewarding both positive and negative engagement, it is no surprise that the tradwife has become so famous. However, it is not just our unexpected fascination with the tradwife figure alone that makes this trend so important. It is the fact that the tradwife aesthetic fits into a continually popular anti-feminist social media trend, a trend that also highlights our cultural guilty pleasure of controversy. We have seen it before on TikTok with Andrew Tate’s sexist rage bait. Although marketed to a different audience (young men) its methods and results were similar: challenge modern feminism, be controversial, and be entertaining. And this it succeeded at: the Guardian reported that Tate’s TikTok videos had been viewed 11.6 billion times. As these anti-feminist figures are catapulted into the mainstream, they bring with them a more palatable taste of the red-pill culture they are derived from, as well as the opportunity for viewers to delve deeper into this incel community.

With both the tradwife and Tate’s content positioned somewhere in between genres of entertainment and politics, it becomes easy to unconsciously imbibe their beliefs – even though most of us understand to some degree the conservative subtext of their content. As O’Dwyer reminds us, we are using TikTok for amusement and we are not willing to consider the content seriously in its politics. We just want to consume; we ‘don’t want to think’. However, there are some who go beyond this passive consumption. There are countless reports of young men originally encountering Tate’s content innocently but then becoming active supporters of his beliefs. Oppenheim quotes Rosie Carter when she describes how Tate appeals to the insecurities of young men with his ‘confidence, his money and his lifestyle’, affirming that his persona is ‘carefully crafted to make his brand of hateful content seem aspirational’.

With 45% of men holding a positive view of Tate, it is tempting to draw links between the way our society chooses to consume this right-wing media so mindlessly and the rise in conservative ideals among young men. For young women, who remain predominantly more liberal, this guilty pleasure hasn’t seemingly translated into real beliefs yet. As seen in the comment section of tradwife influencer Hannah Neeleman, most young women do not support the tradwife’s politics – one comment even asks ‘why should women do all these tasks […] I feel like we are in 1924’In this sense, the tradwife figure might be seen as less successful than Andrew Tate who had a real influence on the values of young men. But her online importance cannot be ignored. The tradwife infiltrated mainstream media as yet another female aesthetic for young women, as a sister to the ‘clean girl’ figure and an antidote to the Brat girl. This cannot be overlooked. Given the rising trend of anti-feminist media, the return of female-targeted right-wing content to the mainstream is shockingly inevitable. It is possible that, next time, its entertainment value might be even more irresistible than the aesthetics of the tradwife or Tate and its marketing might even be enough to convert the liberal politics of the young female audience. So perhaps we must take the tradwife’s presence as a warning of the future. Whether we will actually take this warning seriously and whether we will be willing to ‘think’ differently about our consumption of social media, is another question.