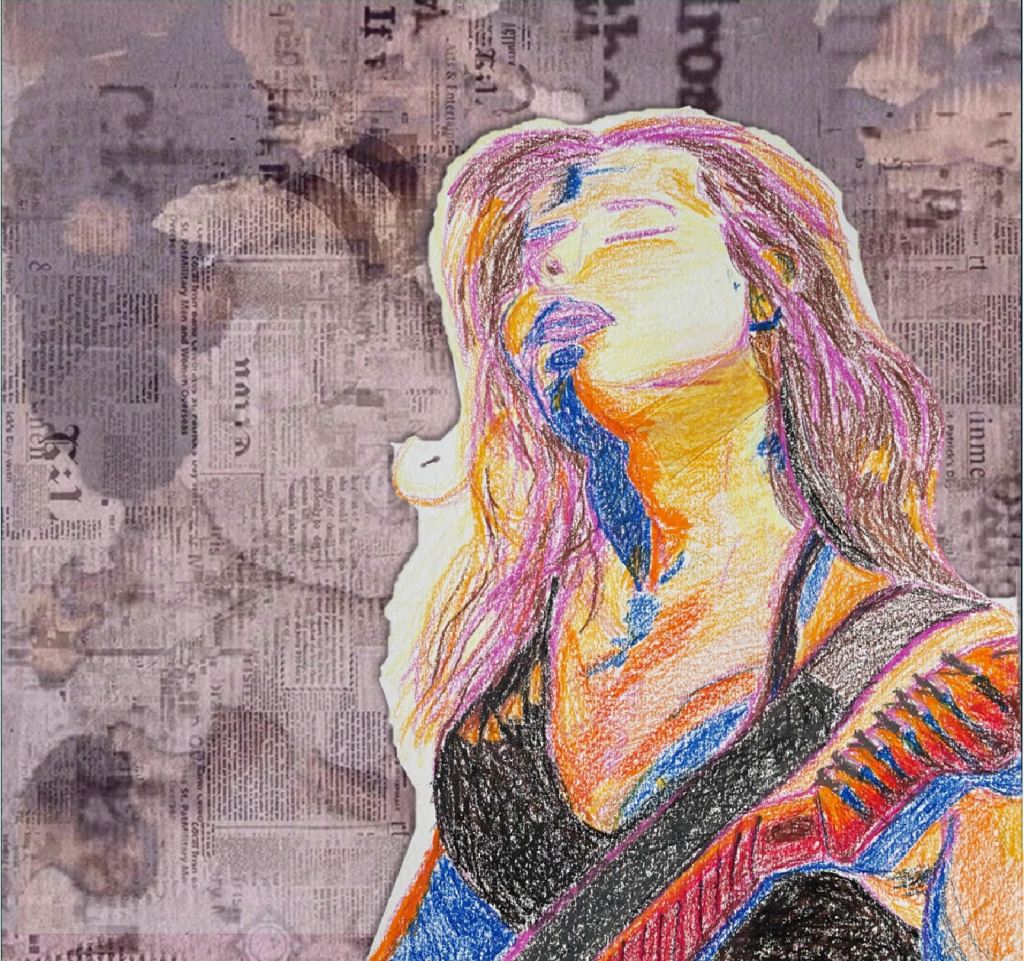

Sofia Lambis explores the over-emphasis on defining female artists’ mental state and prescribing autobiographical readings onto their art.

Studying Plath’s work during my A-levels meant I learnt about her personal life, struggles with depression and eventual suicide. A lot of the literary criticism I read seemed to conflate these personal experiences with her work, reading it as purely autobiographical. There was the impression of poetry scribbled down in a heightened emotional outburst. An outlet for her own inner turmoil.

The works of many female artists are overshadowed and even eclipsed by their deaths. I learnt about Plath’s suicide before her poems and Virginia Woolf’s drowning before her novels. It seems that when looking at the words of these great female authors, we can’t help but read them through an autobiographical lens. This is arguably less common for male authors whose work is recognised for its own merit rather than viewed as the inevitable product of their personal struggles.

With its images of dead children coiled like serpents, empty pitchers of milk and dying flowers, “Edge” is a poem that often falls foul of this habit. It was written six days before Plath’s death, and opens with the lines:

“The woman is perfected.

Her dead

Body wears the smile of accomplishment,

The illusion of a Greek necessity

Flows in the scrolls of her toga,”

It’s understandable why so many read this as autobiographical, as Plath foreshadowing her suicide. But if you look closer, you’ll find allusions to “Medea”, to Shakespeare’s “Antony and Cleopatra”, and to words and writing. Is there another way of reading it? Could the ‘scrolls’ and ‘empty’ milk pitchers and ‘dead / Body’ be referencing writing and creativity? ‘Body’ also refers to collections of written work, bringing to mind the Latin similarity between ‘corpus’ and ‘corpse’. Was Plath writing about the creative process, the death of creativity? Confining ‘Edge’ to being merely a suicide poem is reductive. ‘Edge’ is not poignant because she died – it’s poignant and interesting because of its intertextuality, wordplay, use of metaphor. It’s enough on its own.

Her novel The Bell Jar is another example. I first read it apprehensively expecting a bleak, graphic and tortured narrative. I didn’t think it would be funny. While it does cover serious and heavy topics, it’s also full of wit and scathing one-liners and moments of comedy. Like her poetry, it’s complex and layered. It isn’t just one thing. It even (spoilers) ends on a hopeful note. One of the best passages is the often-quoted fig analogy where Esther Greenwood says:

‘I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked [… ]I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.’

Often interpreted as a symbol of existential choice, this analogy has been co-opted by young people as a metaphor for indecision and hopelessness. Worry over choosing a path, wasting potential and being fulfilled resonates with them, but a consequence of this is that Plath (not Esther Greenwood) has become a figurehead for depression. In her biography of Plath, Anne Stevenson boldly says ‘the idea of suicide formed in her mind like the ultimate and irrevocable fig.’ Conflating Plath’s personal life with the analogy created for her fictional protagonist, Stevenson feeds into the image of her as a tortured poet. Her work ceases to be defined by its creativity and ingenuity and instead becomes part of a self-destructive narrative that culminates in suicide. But, if you turn the page in The Bell Jar you’ll find the lines:

‘I don’t know what I ate, but I felt immensely better after the first mouthful. It occurred to me that my vision of the fig tree and all the fat figs that withered and fell to earth might well have arisen from the profound void of an empty stomach.’

Esther was hungry. Plath was making a joke. The fig tree remains a relevant analogy and perhaps genuinely expresses Esther’s anxieties, but nonetheless it’s been taken out of context. It was meant to be funny. Stevenson’s comment perfectly encapsulates the danger of conflating Plath’s personal life and her creative work. In this reading, her work becomes part of one long narrative chronicling her own personal struggles. It ceases to be original, creative, thought-out. It’s reductive. That isn’t to say that Plath’s work can’t be read as autobiographical, or that it wasn’t intended to be, but reading it as purely autobiographical reduces its complexity and confines it to one interpretation.

The same can be said about Virginia Woolf. In 2015 Wayne McGregor’s ballet Woolf Works opened at the Royal Opera House in London. Split into three parts, it was inspired by Mrs Dalloway, Orlando and The Waves. Yet, Woolf was included as a character and at one point her suicide note was read out. The prologue of Micheal Cunnigham’s book The Hours (a tribute to Mrs Dalloway) imagines the day of Woolf’s suicide. Katie Mitchell’s production Waves featured Woolf as an onstage character narrating extracts from her diary. Each of these examples shows Woolf inserted into a piece about her work. This coupling of the personal with the public is arguably a violation of her privacy. Why should her personal struggles be showcased alongside her work as if they’re another performance? I don’t believe the suicide of male artists like Ernest Hemmingway eclipses their work to the same extent. ‘Hunting for traces of autobiography’, as Sam Jordison puts it, does their work a disservice. It fails to appreciate the complexity, effort, or creativity behind their writing, and suggests they can only write inside their own experiences. Plath and Woolf were craftswomen whose poetry and prose were worked over, edited and intentional. No hysterical outbursts or flights of fancy. Disregarding their creative processes reduces the idea of them as creatives. They weren’t just spilling words onto a page but manipulating language and playing with metaphors and images. Their works aren’t remembered, adapted and made relevant because of their deaths. They stand up on their own.