Stella Rogers illuminates the oversimplification of methods used by the Black Panther Party in the popular mindset and media. With the BPP’s legacy clouded by accusations of misogyny and violence, this article seeks to bring to light the highly impactful scope of the group’s community projects and their pivotal role in the advancing black liberation.

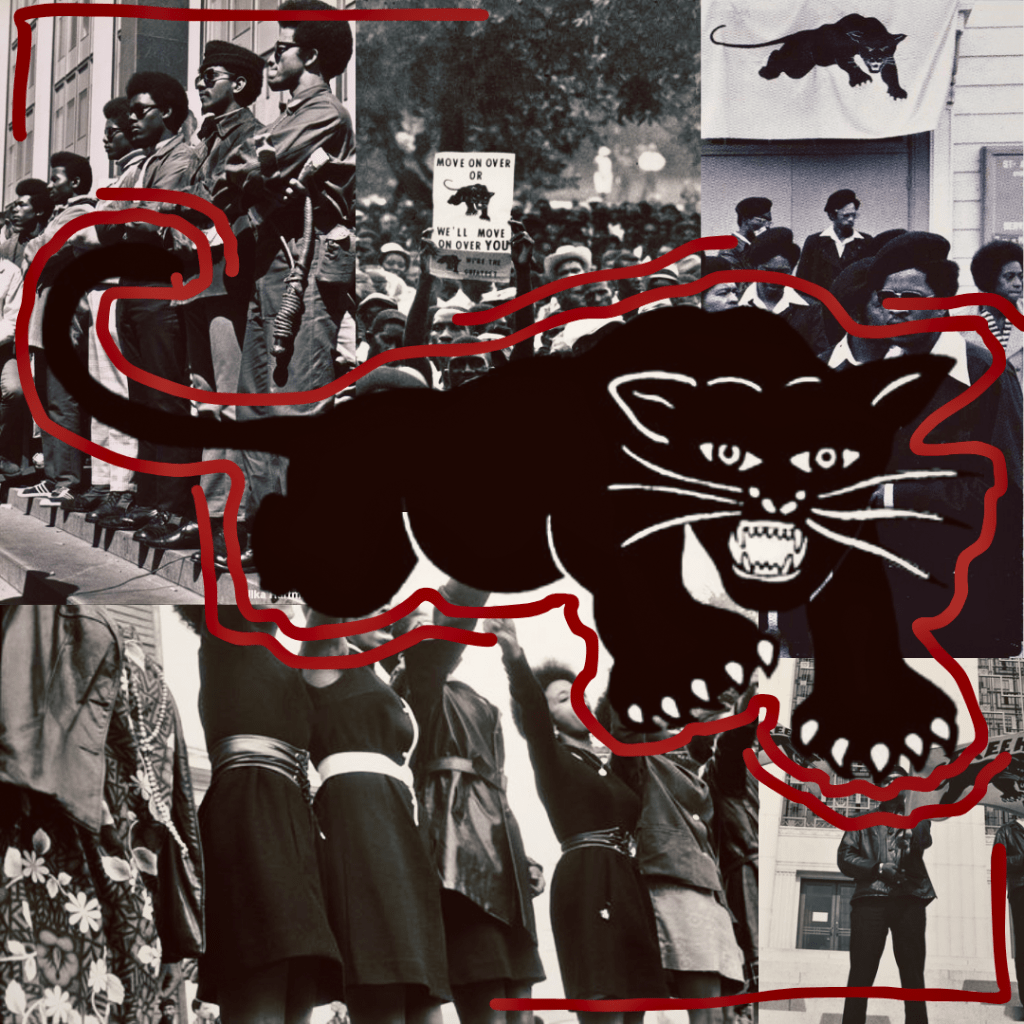

The image of the Black Panther Party and the Civil Rights Movement has remained prevalent in popular media and public consciousness. However, often these representations of the Panthers and their role within the Civil Rights Movement simplify the Black Panther Party’s doctrine and practice.

Since the party’s conception, abundant oversimplification of the Black Panthers has occurred in film, which are many people’s primary source of information regarding the party. Most notably, Marvel’s Black Panther loosely uses a binary retelling of the Civil Rights Movement as peace vs violence to create a blockbuster superhero film. This oversimplifies the Civil Rights Movement to being a battle between the pacificist ‘Martin Luther King Jrs’ and the militant ‘Malcom Xs’, when, in reality, the panthers used a variety of methods beyond just violent protest. Moreover, characters who represent the Panthers are often dismissive and violent towards women, portraying the group as having little regard for women and being dominated by hyper-masculine men. This is not the only example of media stereotyping the Black Panthers as misogynistic. There are the tough, leather-donning men who stand by as an act of domestic abuse occurs in 1994’s Forrest Gump. In the scene, Gump’s love interest Penny is hit by her boyfriend, who is closely affiliated with the Panthers. The members present are passive bystanders during this violent moment and actually kick Penny out of their meeting, implying that the Panthers were indifferent to and even accepting of abuse against women.

In the UK specifically, many students were never offered a richer understanding of the civil rights movement beyond, maybe, a few key figureheads and moments. Therefore, these misrepresentations of the Black Panther Party as misogynistic, violent men in leather have become our primary understanding of the party and their role in the Civil Rights Movement more generally. Often, the party is dismissed as a bunch of sexist, gun-slinging rebels in our popular imagination. This does a grave disservice to the complexities of the party’s gender politics and actions.

The BPP is often remembered as the ‘militant one’ in the black Civil Rights Movement. Most often, people refer to the Panther’s emphasis on gun ownership and tough image. However, a large section of the party’s activism focused on community projects, which provided free healthcare, breakfast and even schooling for many. The positive effects of these programs were wide-reaching for the community. By the end of 1969, the party was feeding 20,000 children breakfast across the country. Moreover, free sickle cell anaemia (a disease that disproportionately affects black people) testing and research led to advances in black healthcare and knowledge about the disease. These benefits for the black community in many areas across the U.S would not have been felt without the BPP.

Support for these schemes was strong and displayed the Panther’s commitment to the community they served. With the community onside, the Panther’s direct action not only exposed the failings of the US government by displaying a desperate need for these services, but also created spaces in which to discuss ideas of black liberation and class struggle. This is not to say that the more militant actions of the BPP were insignificant; patrolling police was an essential task in keeping African American communities safe. However, if we only focus on this one aspect of the Panther’s practice, a comprehensive understanding of the BPP is impossible.

A large reason why, I believe, the community programs carried out by the BPP is not as often portrayed in popular culture, is because these acts of cooking and organising for the community is associated with femininity. This aspect of the BPP is less ‘fun’ to show in film and TV and, in rebellious politics more generally, seen as less significant. However, these programs were essential in educating the community and ensuring their survival in the racist system they were being oppressed by. These community efforts also deviate from the idea of the Black Panther’s masculinised, ‘macho’ image, as men within the party were involved in the stereotypically feminine acts of cooking and organising projects for a purposefully impoverished community to benefit from. These projects also led to women being heavily involved in the Panther’s activity, deviating from some black liberation movements at the time which gatekept women from their groups.

Building on the gender politics of the BPP, it must be recognised that the dismissal of the Panthers as hyper-masculine and misogynistic fails to portray the complexity of the party’s gender dynamics. It is true that the Panther’s did have issues internally relating to sexism and gender stereotypes. Often, communal living situations had women taking on the stereotypical role of cooking and cleaning for the house. Black feminism arose, in part, with black women’s dissatisfaction with the black liberation movement’s treatment of them.

However, the party had women involved in leadership, which was not common in black nationalist movements at the time, with Elaine Brown becoming leader of the party in 1974. Oftentimes, propaganda images released in the BPP include gun-wielding women looking as tough as the men, encouraging women to use the constitution to their advantage and arm themselves in the name of self-defence. In fact, 66% of the party were women, according to Angela Davis. Whilst the BPP most definitely had a tricky relationship with gender, it would be reductive to dismiss them as wholly misogynistic. If anything, the failings of the BPP to fully integrate gender issues into their practice presented a learning opportunity for movements that came after it.

In conclusion, it is clear that the Black Panther Party remains a deeply misunderstood movement. The echoes of their community projects ring clear today, even if we aren’t fully aware of their origin. Dismissing the BPP’s membership as hyper-masculinised, sexist men not only ignores the great number of prominent women within the party, but also reduces the complexity of the gender politics in the BPP. Both the good and bad the Panther’s did regarding its women inspired and mobilised feminist movements after it. In many ways, the BPP were ahead of the times in how women could hold leadership positions. This Black History month, revisiting the struggles of the Civil Rights Movement and aiming to understand them holistically remains paramount, as the UK education system has historically misrepresented even the most prominent groups in black history.

Sources :

– https://www.vox.com/2016/2/14/10981986/black-panthers-breakfast-beyonce

– https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/27/activist-elaine-brown-you-must-be-willing-to-die-for-what-you-believe-in– https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/sep/04/sisters-revolution-women-of-black-panther-party