TWSS’ Sophie Morland investigates the gap in authority between male and female voice. With an exploration of socialisation differences, disparities within professional roles and the everyday societal distaste for female power, the article poses the question: Who gets to speak?

“Speak up”. Speak up for your rights, speak up to be heard, speak up to be respected. This phrase has dominated Western feminist rhetoric for decades, promising women a solution to their problems if only they were ‘brave’ enough to speak up. And we have- fiercely, hesitantly, competently, quietly, loudly, in solidarity and alone, and in all the exhaustive aspects of life in which we are scrutinised more than our male counterparts. Sounds like it should do the job, yet why are women’s voices so often not listened to?

When we imagine the supreme voice of authority our mind most likely dreams up a 1. Middle-aged, 2. Middle-class, 3. Educated, 4. White, 5. Male. Mine would probably wear a suit and stand at a podium. Somehow, a default image has emerged of a competent individual who can speak on behalf of universal human experience. This self-assured male figure can calmly command the attention of the masses, effectively promoting his interests while maintaining an admirable composure. He is so powerful that he has gradually defined what it means to embody ‘confidence’ and this has become culturally ingrained and accepted so as to benefit his type and other those with contrary mannerisms and modes of speech. Notably, women are the largest group to fall into this category.

The case studies of the incompatibility of women’s voices with the nature of modern politics are multiple. They serve as an example of the intense susceptibility to criticism women are subject to when having achieved success. Where Hilary Clinton’s strident speech was labelled ‘grating’, former Plaid Cymru leader Leanne Wood’s voice was branded as ‘warmer than sunlight shining through a jar of honey’, which led to her reputation as the passive darling. It seems as if for women in politics to balance confidence, likeability, and assertiveness without falling into the labels of ‘pushy’, ‘meek’ or ‘sexless’ is near impossible. We can see that where the substance of the language of male politicians is dissected, there is a far greater emphasis on women’s pitch and intonations in comparison. One could argue that since this is the most physical aspect of linguistic performance it is therefore the most scrutinised. Most women will be familiar with the pathetic typification of ‘shrill’, a word that inevitably taps into stereotypes of female hysteria and delusion. In fact, Margaret Thatcher famously underwent speech therapy in the 1970s, hoping to widen her electoral appeal. By making her voice firmer and rejecting the archetype of the ‘shrill housewife’, she sought to narrow the gap of authority with her rival Jim Callaghan. Though a tactful decision, she ultimately worked within the confines of her oppression as a woman by impersonating a man in order to achieve respect. Yet should we not seek to remove ourselves entirely from these ingrained prejudices? Should we not strive to figure a female voice that can be judged equally powerful without losing its feminine essence?

This distaste for women’s authority is of course not confined to solely elite, intellectual spaces. Unfortunately, avoiding a political career, board room debates and fancy dinner parties will not assure your security. It happens everywhere and all the time. A recent viral video posted by professional golf player Georgia Ball has opened up a discourse on ‘mansplaining’, moving the word into the wider cultural lexicon. I feel like I could write a whole psychoanalytic paper delving into their hilarious yet enraging conversation. For those of you who have not come across it, it involves a male stranger giving *very* unwarranted and unnecessary advice on Ball’s swing, before taking credit for her apparently improved second take assuring “see how much better that was.” Unknowingly, this man has created a perfect microcosm for this article and one which has resonated with millions of women around the world. His undisputed assurance that he must know better than this young woman due to his (very confidently mentioned) 20 years of unprofessional experience speaks to our unconscious bias of men’s capability and authority to teach and explain.

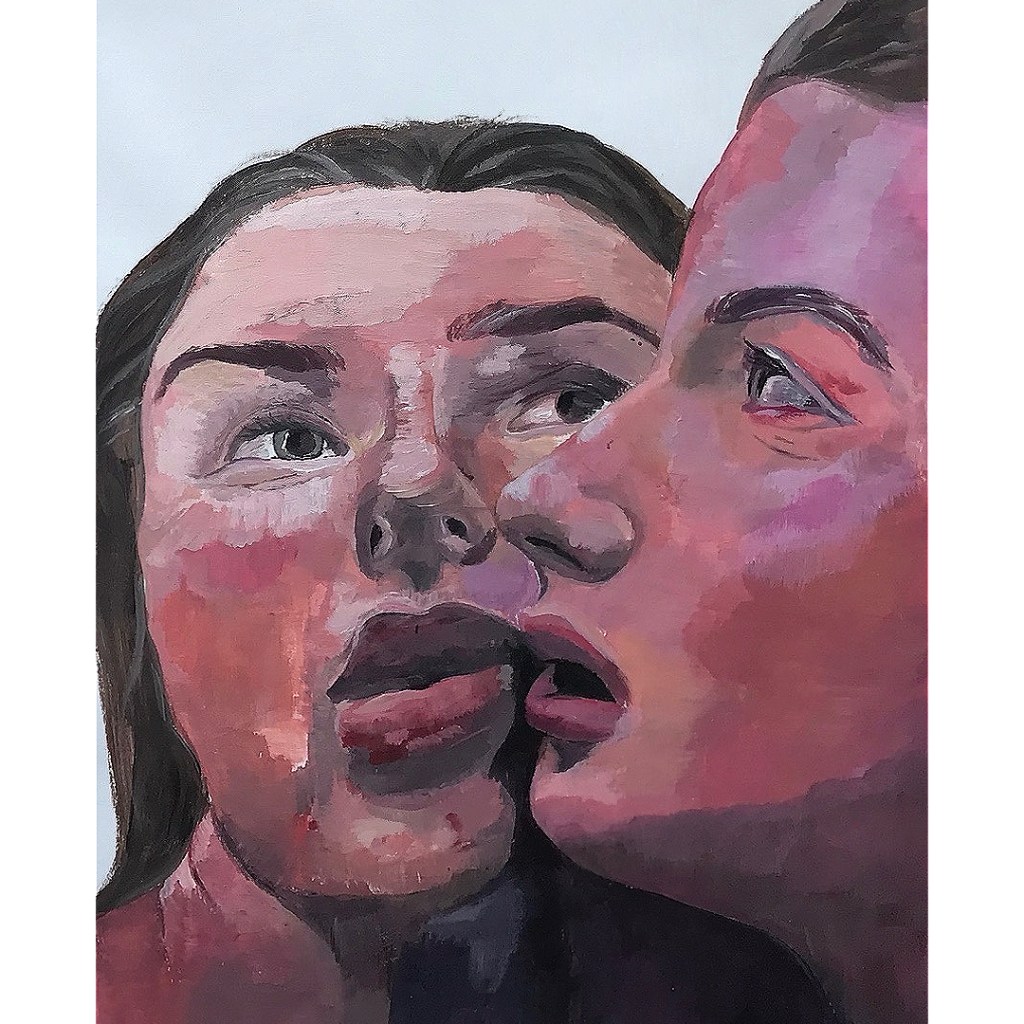

Artwork by Lily Stephens

So how has this happened? Let’s zoom back to the playground, a space where many of us found the voice which helped us form our first human networks. Research has shown vast differences in the socialisation of conversational styles between boys and girls. Where status is emphasised in male friend groups, empathy is valued in females. Girls are taught to emphasise their affinity and downplay their differences, balancing their own needs with those of their peers. Conversely, boys tend to play in larger, often hierarchical friend groups in which leadership and speech are key ladders to popularity. Girls who perform well academically in school are praised for their diligence and conscientiousness whereas boys excel through confidence. We can see that having the notion of status ingrained in men at such a young age may be a factor in their inclination towards individual assertiveness. I am aware that so far this article has brushed over intersectional issues, in particular class, race and disability and their interactions with speech patterns and figures of authority. It is imperative to highlight that women in these minority groups will likely face a disproportionate and multifaceted judgement of voice. This article does not seek to argue that all women are viewed as less authoritative than a man in all situations. This disregards the struggles many men face when trying to be heard as well as the sharp talent of individual women throughout history. Rather, I am trying to highlight that all women will always be at a slight disadvantage in some form because a man’s voice is the preconceived norm.

The bias we have towards the male voice is an unconscious bias for a reason- even the most proud and radical feminists will have it, and this is not something to be ashamed of. As more women enter professional and male dominated environments, these same women adapt themselves to conform to the patriarchal environments that excluded them in the first place. This does not speak to an inherent weakness within women but rather to the weakness of a system that covers up its staticity with illusions of progress that fail to address the issues at the heart of the authority gap. Though undoubtedly there has been so much done for women’s rights, this ingrained unconscious bias remains stuck. It seems as if we have tried to correct prejudiced attitudes politically before wholly recognising them and collapsing them at the root. It is only when we train ourselves to spot these biases that we can truly unpick and correct the system.