TWSS’ Tara Bell, alongside Engendering Change’s Jo Morgan, addresses the disparities in approaches towards our sexual education, emphasising the importance of equal attitudes towards all individuals’ bodies, sexualities and lives.

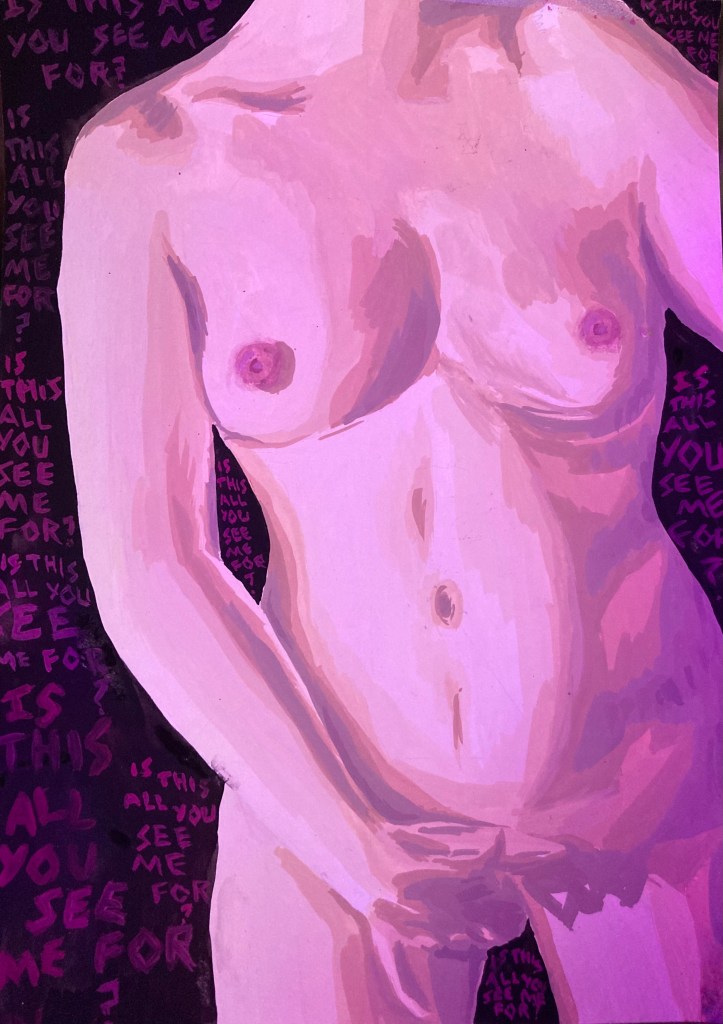

From childhood, we are taught that our bodies are a sight of danger. Through the government’s current denial of the existence of transgender bodies, the growing rates of sexual violence towards women, and the police brutality against Black people, the patriarchal, homophobic, and racist forces interwoven throughout our society resound this fact: that some bodies are less valuable than others. This causes a disconnect between our inner and outer selves, as we lack agency in how our bodies are being increasingly mistreated. And how can you embody a space when it’s not entirely your own? Amongst the various facets of our society that target marginalised bodies in different degrees, one way this self-containment is disrupted is through inequitable sex education.

Fear mongering and risk management are widely used tactics in schools across the UK. Scaring kids into not having sex is clearly prioritised over encouraging them to do it safely: using either graphic pregnancy videos or harmful pro-life rhetoric, many young girls are led to fear their sexuality, and look upon their bodies with shame. One friend even told me that she was given a talk by a woman who underwent conversion therapy, discussing how she has now left her ‘unnatural’ past behind her. It seems that these patriarchal and heteronormative values underpin so many curriculums, which entirely lack compassion as they blame female-identifying students for their sexual expression.

Wanting to know more about how this curriculum can be mended, I chatted to Jo Morgan, the founding CEO of Engendering Change LTD: a company that strives for an empowering sex education, one that is founded upon gender equity and includes queer, Black and female bodies into the conversation. Spending time as a teacher of pastoral care and being invited into various schools to give talks about sexual health, it became clear to her that curriculums across the country were laden with taboos and stigmas. She recalled visiting one school, in which a cross section of the female anatomy was used and the teacher had removed the clitoris from the diagram. As a result, the female body was entirely dehumanised and reduced to a sum of its parts, and it was made clear that the exemplar female body was a white one, which lacked the capacity for sexual pleasure. This experience was not an isolated one: in another school, the headmaster expressed discomfort over Morgan’s inclusion of female pleasure on the curriculum, yet he deemed the male ejaculate an acceptable talking point. It was clear that male sexual pleasure was the accepted paradigm.

When women’s sexual desire is viewed through the lens of the male gaze – that is, for the purpose of male, heterosexual desire – female bodily autonomy is ignored, and lesbian relationships are invalidated and fetishized. Culturally wide perceptions of sex begin to be overwritten by porn narratives, causing the actions of boys to also be influenced by this advocation for masculine sexual dominance. And when your peers, as well as your teachers, neglect to acknowledge the agency of the female body, young girls are led to internalise these attitudes towards themselves.

It raises these questions: why do so many schools across the country uphold a PSHE curriculum which instils guilt, fear, and shame into female students? How can young girls be open with their bodies, when they are taught that some parts of themselves are not worthy of being spoken about? It becomes a process of unlearning, of rewriting the beliefs that enforce this separation between the self and the body, and of rectifying this feeling of being a stranger in yourself. As Claudia Rankine writes in Citizen: An American Lyric, “you begin to move around in search of the steps it will take before you are thrown back. Into your own body, back into your own need to be found”.

What are the necessary steps needed to aid this reintegration? Morgan tells me it’s through an empowering, diverse celebration of each and every body. She approaches this through re-evaluating the whole school culture – the language that’s used and the modelling by staff – that underpins this so-called phallocentrism. This not only tackles the very foundations of each institution and uproots the heteronormative paradigm from its core, but it also instils a sense of community in the school. Long-lasting social change cannot occur without mutual love and togetherness, and in a school environment this is no different; by including every voice into the conversation, liberation can occur at every level.

This is why Morgan also strives to uplift the voices of teachers. It is clear that a lot of damaging lessons result from a generational cycle; if you were educated through a heteronormative, white-centric curriculum yourself, then you might not hold the necessary tools to educate students through an empowering lens. As an increasing number of schools in the UK are extremely underfunded and understaffed, this process of relearning becomes harder and harder to navigate, and Morgan realises the importance of equipping teachers with the necessary tools to deliver an inclusive education. If the teachers are not speaking from a place of authenticity, then students will never be willing to take their words on board.

In a culture that consistently implores us to ignore how our body feels, it’s important to encourage students to tap into their own authenticity too. Morgan employs trans and non-binary speakers to deliver student talks, which opens the conversation surrounding the fluidity of identity and helps queer students to feel seen. The nature of a school environment only renders this more necessary, as conforming to the mainstream culture can often feel as fundamental as breathing. Social validation becomes a lifeline, so much so that for me, I didn’t realise I was queer until I was eighteen, as the heteronormative social currency consistently encouraged me to turn away from myself.

Creating an open, judgement free dialogue is so important. When the sexual health curriculum becomes focused on teaching positive action instead of risk management, space can be created for students to explore the intricacies of their identity. Morgan encourages students to embrace their sexual agency and the agency of future partners: students ask themselves “what do I like?” and “what do I not like?”, because if that is the starting point – an awakened, self-aware curiosity – then you’re not passive, you’re active in how you express your sexuality. And then, I would say, you can begin to connect to your body again.