Through interviews and looking at the student-body experience, Eve Davies discusses how strike action has effected the humanities; the degree subjects dominated by women.

It’s the last day of term. You’re finally finishing a year at university, perhaps even coming to the end of your degree course. You should be happy, grabbing a pint with your coursemates at the end of the day. But despite having worked relentlessly for this, the possibility of not knowing when you will receive your results for many months looms. Of course, the wait for degree or exam results is daunting for every student, but these anxieties were exacerbated this year by the marking boycott. Indeed, many students are still unaware of their results for modules. Which subjects have been affected? A broad range – from psychology to Spanish. However, it seems that arts, humanities, and social sciences students have been most impacted. Many STEM lecturers have opted out of striking, arguing that face-to-face teaching is essential in those subjects. Humanities students are thus left paying equal fees to their STEM counterparts, yet receiving half the experience. While the number of women in STEM subjects is ever-increasing, humanities have been consistently dominated by female students. We must ask why humanities students (and by extension, once again, female students) are being sidelined?

The last three years have been difficult for everyone, particularly university students as the effects of COVID-19 have resulted in a disjointed, incomplete university experience. Just as cafés began to open and weekend socialising in pubs and bars was returning, seminars were cancelled, lectures were (once again) online, and essays were left unmarked. Imagine facing all of these disruptions in the pandemic years, only to face an even more disrupted education as soon as you come out of it – no wonder so many are feeling disheartened.

While many would assume that fewer contact hours would mean that arts, humanities, and social sciences students were minimally affected by the strike action, the reality is far from that. Essay and assessment-based feedback catalyse improvement in these subjects. When asked about how they were affected by the strike action, second-year humanities student, Jack Lester, stated that “one of [their] units only had two of the twelve seminars”. Like most humanities students, Jack ended their first year of university disappointed: “I’m still waiting for two of my unit marks as well. It’s just frustrating, I feel like they’ll never be marked now. We originally had fewer contact hours than maths and medicine, for example, and now they’ve barely lost lesson time. It feels like STEM is seen as more important.”

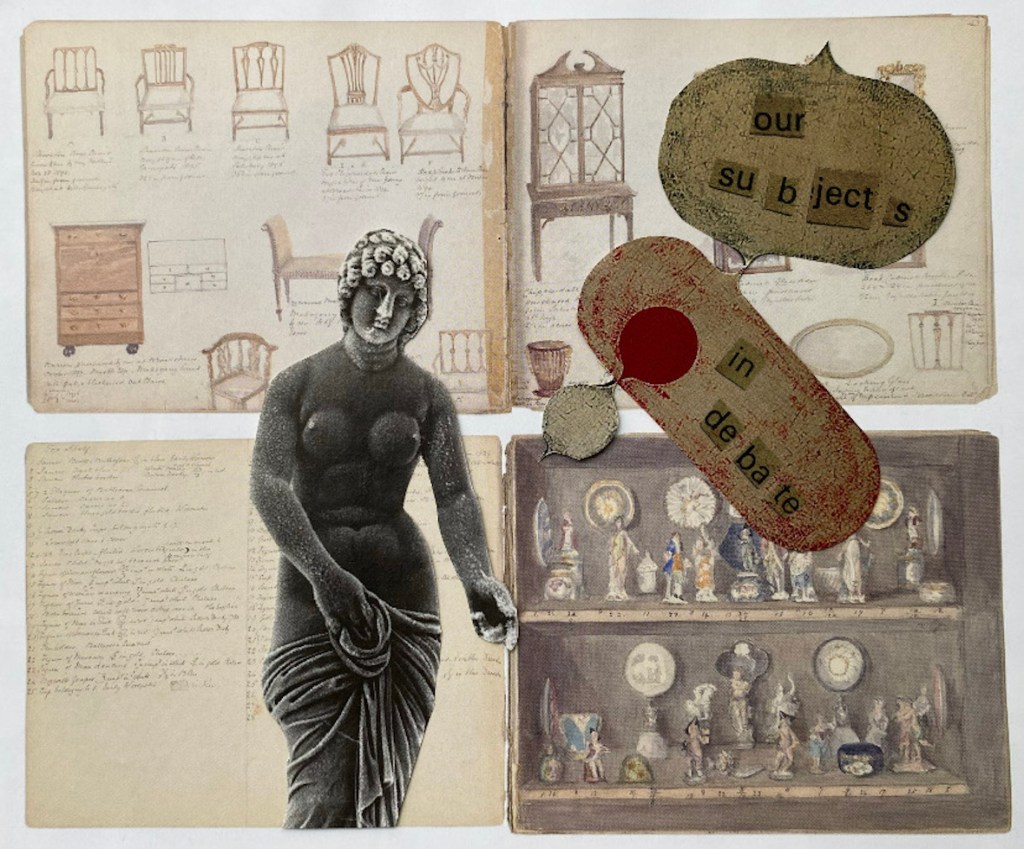

Is this a symptom of a larger problem? Humanities students are constantly trying to defend their right to be perceived as equals to their STEM peers. We are constantly quizzed about our plans for the future, berated about our “impractical” ambitions, and condescendingly asked how we would possibly get a job in the current climate. It is infuriating to hear the Prime Minister vow to phase out humanities degrees on national television, arguing that they do not improve students’ “earning potential”. In 2015, the British Council conducted a study of 1,700 people from 30 countries, finding that the majority of those in leadership positions had either a social sciences or humanities degree. It’s unsurprising, considering the necessity for emotional intelligence and communication skills in these leadership positions. Yet, the reputation of these subjects for being “unserious” or a “waste of time” remains.

Female-identifying students dominate the humanities and social sciences – the subjects worst hit by industrial action. Arts, humanities, and social sciences all have more than 50% female students across all continents, compared to the 20% female students that study engineering and the 22% that study computer science. The skills that are utilized within these subjects are traditionally feminine: creativity, communication, and tolerance. Once again, it seems these skills are being undervalued and, therefore, women are being sidelined. Watching your male peers freely attend lectures and seminars, while you’re stuck at home viewing poor recordings and writing essays with no support, only to find that those essays may never be marked, is devastating.

I fully understand the justifications behind the strikes and support university staff wholeheartedly as they fight for fair pay and working conditions, but I can’t deny that I am anxious about the upcoming academic year. We are already hearing murmurs of further UCU striking this term and I do not want my first year of university to be entirely remote, especially when my flat-mates are constantly on campus for lab visits and experiments. No one is denying the importance of STEM students’ practical work; ultimately, the same amount of money is leaving our bank accounts, so it seems rather unfair that humanities students are saddled with more significant effects.