Rosie Pundick unpacks the toxic glamorisation of women’s mental health in the media. By comparing modern film and TV with classic literature, she explores how this trope has manifested and developed overtime.

The depiction of the young woman with smudged makeup and perfect hair, smoking a cigarette, is a familiar one in film and television. It is an image that is often used to portray a woman who is struggling with mental health or substance abuse. It is such a familiar image that it has thus become an attractive one. The association of this image with mental health has led to the glamorisation of a woman who looks like this, despite it being far from the reality of what a woman struggling with their mental health looks like.

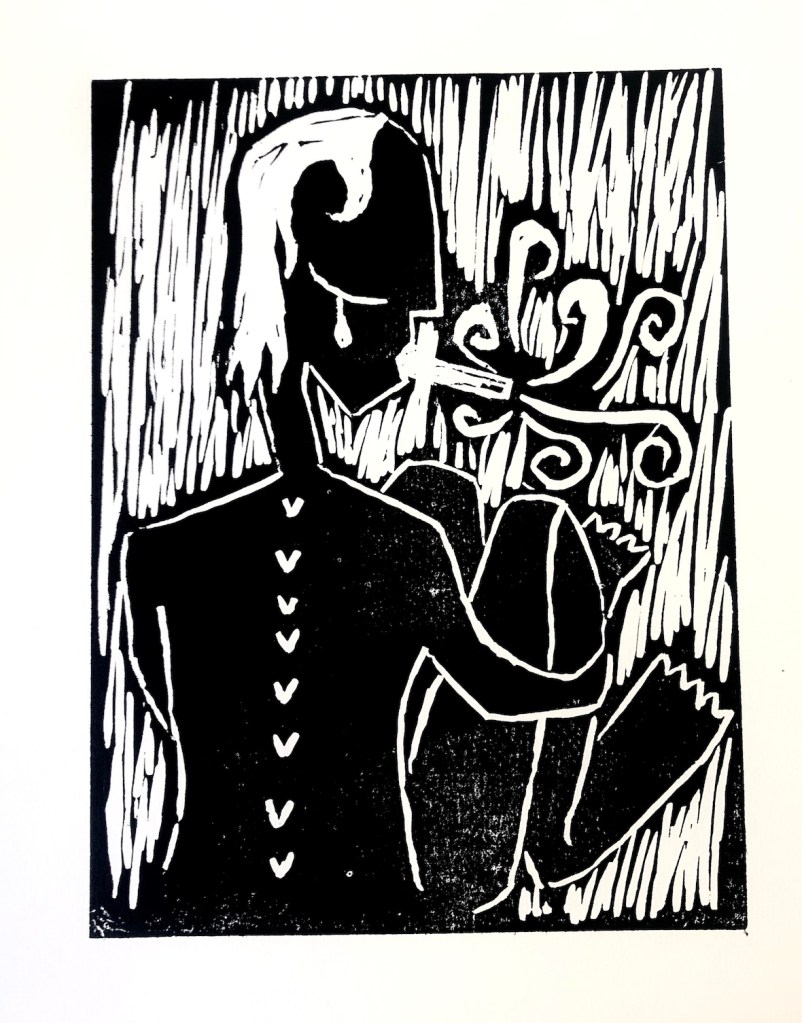

In film and media, this image is typically depicted by women created by men. Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) comes to mind, with the famous image of Mia Wallace lying on her front with a cigarette in her hand. A more recent example is Beth Harmon in the Queen’s Gambit (2020), created by Scott Frank and Allan Scott. These women, that both succumb to substance abuse are projections of male desire, resulting in the enjoyment of the male audience. The male gaze is empowered by the male creation of these women that thus results in a falsified reality of what a woman who is struggling with addiction looks like. This leaves women to attempt to live up to that reality, resulting in the internalisation of what men desire – the internalisation of the male gaze.

Beth Harmon, the protagonist, is pictured in Episode 6 as smoking a cigarette on the couch, with her hair perfectly done, eyeliner immaculate and wearing lingerie – a representation of her declining into substance abuse. Her legs are smooth and shaven and despite this supposed downfall, she looks perfect. When I picked up Simone de Beauvoir’s book The Woman Destroyed, the front cover depicted the same image – a woman with a short, sleek bob in fashionable clothing, smoking a cigarette. I therefore feared the destroyed women who are depicted in three short stories, were going to similarly glamorised. Surprisingly, Beauvoir’s presentation of the women was refreshingly honest and real. In the title story, Monique, who experiences losing her husband to another women and thus falls into a depressive state, is portrayed as messy and emotional. Her experience of depression is a far more relatable one as she describes not being able to get out of bed, being unable to eat or get dressed and having little desire to feel joy.

The male gaze in television reinforces an audience’s fulfilment of aesthetically pleasing images. But must aestheticism detract from reality? Clearly, reality has no place in a man’s perception of women. Beth is not presented as perfect during her downfall, but also is dressed to appear attractive. The scene that I found the most striking was her dancing around her house, cigarette and drink in hand, then throwing up in one of the trophies. She wipes her mouth but continues to look perfect. Even as she is throwing up, the directors’ ideal of a woman has resulted in her sexualisation at this moment.

This presentation is damaging to all genders; it promotes the idea that women look attractive through men’s eyes when they are abusing substances, which reality disproves, which, by extension glorifies substance abuse in itself. It is simply unrealistic and dehumanises women; are women not allowed to look messy and unattractive? It inevitably leads to women attempting to live up to this standard to achieve what society instructs them to do (the pleasing of men), resulting in the internalisation of the male gaze.

In comparison, Beauvoir presents a more authentic depiction of a woman who is struggling with depression. There is no glamorisation in Monique’s story; both Beth and Monique are women from the 1960s, yet one is real and one is fabricated to a man’s desire.

Monique’s story is construed through diary entries that permits an exploration of her own mind. Contrastingly, Beth’s private moment is portrayed through what she is wearing and what she looks like, enhanced by the bird’s-eye view shot – her legs are propped up so her underwear is visible, which creates the effect that this moment is not about her, but appealing to male desire – the male audience gives power to the male gaze that constructs this image. Monique’s depression is described honestly and throughout the story, there is very little happiness: “it will always be dark” (page 207) “I’ve lost my own image” (page 220). The story ends with the declarative sentence “I am afraid.” Whilst the lack of the happy ending is perhaps more upsetting to readers than Beth’s happy ending of winning the championship, it is far more honest. Depression does not always have a happy ending, nor does substance abuse and thus the skewed depiction of this in Queen’s Gambit promotes unrealistic expectations around how women process mental health issues.

The male gaze is present in “The Woman Destroyed” however it is internalised by Monique, which she reflects upon. She states in one of her diary entries “He sees me at one o’clock in a dressing-gown and with my hair undone.” This is strikingly different to Beth – she is simply a product male desire through the male gaze.

The difference between the presentation of Beth and Monique can be explained in their conception. Beth was created by two men, whereas Monique was created by a woman. As 70% of the film and TV industry is still dominated by men, this disparity is unsurprising. It is essential that the way women are presented is put under scrutiny in order to minimise the unrealistic expectations of women and the damage that the male gaze causes. This inequality must be resolved if it is the only way that women can be represented as their true selves in the media.